Professor of Finance at the Stern School of Business at NYU

Sovereign Ratings, Default Risk and Markets: The Moody's Downgrade Aftermath!

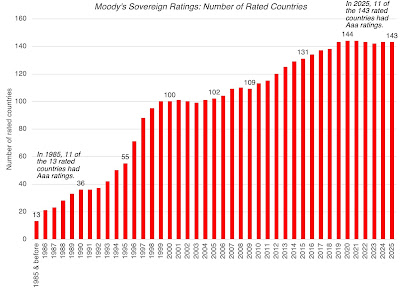

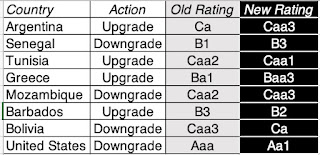

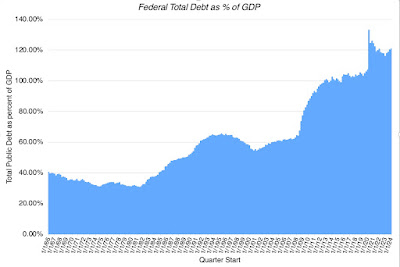

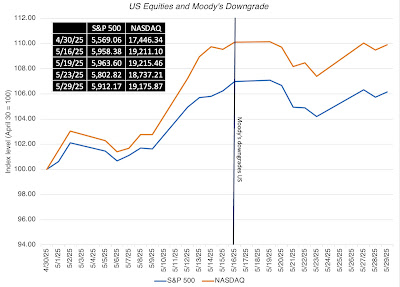

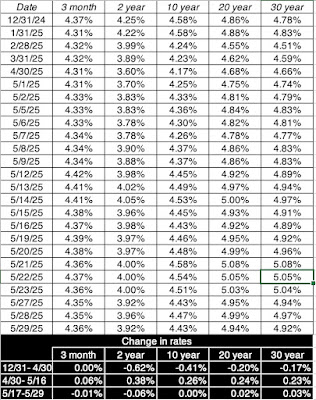

I was on a family vacation in August 2011 when I received an email from a journalist asking me what I thought about the S&P ratings downgrade for the US. Since I stay blissfully unaware of most news stories and things related to markets when I am on the beach, I had to look up what he was talking about, and it was S&P's decision to downgrade the United States , which had always enjoyed AAA, the highest sovereign rating that can be granted to a country, to AA+, reflecting their concerns about both the fiscal challenges faced by the country, with mounting trade and budget deficits, as well as the willingness of its political institutions to flirt with the possibility of default. For more than a decade, S&P remained the outlier, but in 2023, Fitch joined it by also downgrading the US from AAA to AA+ , citing the same reasons. That left Moody's, the third of the major sovereign ratings agencies, as the only one that persisted with a Aaa (Moody's equivalent of AAA) for the US, but that changed on May 16, 2025, when it too downgraded the US from Aaa (negative) to Aa1 (stable). Since the ratings downgrade happened after close of trading on a Friday, there was concern that markets would wake up on the following Monday (May 19) to a wave of selling, and while that did not materialize, the rest of the week was a down week for both stocks and US treasury bonds, especially at the longest end of the maturity spectrum. Rather than rehash the arguments about US debt and political dysfunction, which I am sure that you had read elsewhere, I thought I would take this moment to talk about sovereign default risk, how ratings agencies rate sovereigns, the biases and errors in sovereign ratings and their predictive power, and use that discussion as a launching pad to talk about how the US ratings downgrade will affect equity and bond valuations not just in the US, but around the world.

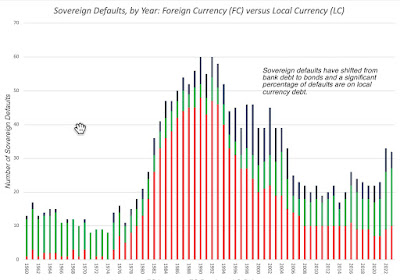

Sovereign Defaults: A History

|

| BoC/BoE Sovereign Default Database |

- Default has a negative impact on the economy , with real GDP dropping between 0.5% and 2%, but the bulk of the decline is in the first year after the default and seems to be short lived.

- Default does affect a country’s long-term sovereign rating and borrowing costs . One study of credit ratings in 1995 found that the ratings for countries that had defaulted at least once since 1970 were one to two notches lower than otherwise similar countries that had not defaulted. In the same vein, defaulting countries have borrowing costs that are about 0.5 to 1% higher than countries that have not defaulted. Here again, though, the effects of default dissipate over time.

- Sovereign default can cause trade retaliation . One study indicates a drop of 8% in bilateral trade after default, with the effects lasting for up to 15 years, and another one that uses industry level data finds that export-oriented industries are particularly hurt by sovereign default.

- Sovereign default can make banking systems more fragil e. A study of 149 countries between 1975 and 2000 indicates that the probability of a banking crisis is 14% in countries that have defaulted, an eleven percentage-point increase over non-defaulting countries.

- Sovereign default also increases the likelihood of political chang e. While none of the studies focus on defaults per se, there are several that have examined the after-effects of sharp devaluations, which often accompany default. A study of devaluations between 1971 and 2003 finds a 45% increase in the probability of change in the top leader (prime minister or president) in the country and a 64% increase in the probability of change in the finance executive (minister of finance or head of central bank).

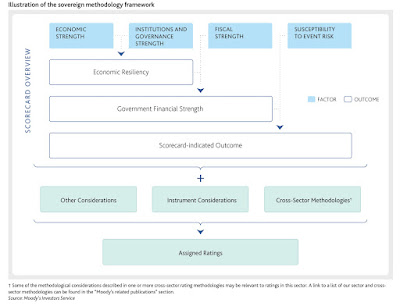

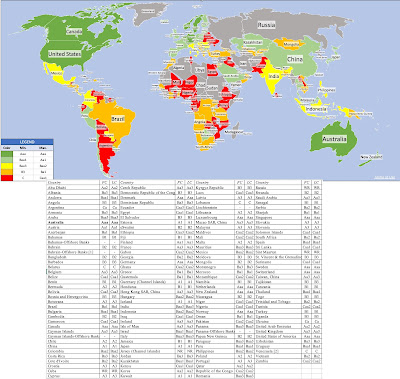

Sovereign Ratings: Measures and Process

- They have been assessing default risk in corporations for a hundred years or more and presumably can transfer some of their skills to assessing sovereign risk.

- Bond investors who are familiar with the ratings measures, from investing in corporate bonds, find it easy to extend their use to assessing sovereign bonds. Thus, a AAA rated country is viewed as close to riskless whereas a C rated country is very risky.

|

| Moody's sovereign ratings |

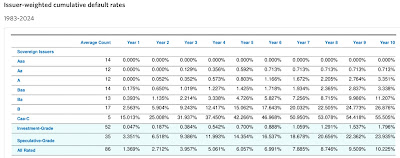

- Ratings are upward biased : Ratings agencies have been accused by some of being far too optimistic in their assessments of both corporate and sovereign ratings. While the conflict of interest of having issuers pay for the rating is offered as the rationale for the upward bias in corporate ratings, that argument does not hold up when it comes to sovereign ratings, since not only are the revenues small, relative to reputation loss, but a proportion of sovereigns are rated for no fees.

- There is herd behavior : When one ratings agency lowers or raises a sovereign rating, other ratings agencies seem to follow suit. This herd behavior reduces the value of having three separate ratings agencies, since their assessments of sovereign risk are no longer independent.

- Too little, too late : To price sovereign bonds (or set interest rates on sovereign loans), investors (banks) need assessments of default risk that are updated and timely. It has long been argued that ratings agencies take too long to change ratings, and that these changes happen too late to protect investors from a crisis.

- Vicious Cycle : Once a market is in crisis, there is the perception that ratings agencies sometimes overreact and lower ratings too much, thus creating a feedback effect that makes the crisis worse. This is especially true for small countries that are mostly dependent on foreign capital for their funds.

- Regional biases : There are many, especially in Asia and Latin America, that believe that the ratings agencies are too lax in assessing default risk for North America and Europe, overrating countries in those regions, while being too stringent in their assessments of default in Asia, Latin America and Africa, underrating countries in those regions.

|

| IMF |

- Lack of surprise effect : While the timing of the Moody's downgrade was unexpected, the downgrade itself was not surprising for two reasons. First, since S&P and Fitch had already downgraded the US, Moody's was the outlier in giving the US a Aaa rating, and it was only a matter of time before it joined the other two agencies. Second, in addition to reporting a sovereign rating, Moody's discloses when it puts a country on a watch for a ratings changes, with positive (negative) indicating the possibility of a ratings upgrade (downgrade). Moody's changed its outlook for the US to negative in November 2023, and while the rating remained unchanged until May 2025, it was clearly considering the downgrade in the months leading up to it.

- Magnitude of private capital : The immediate effect of a sovereign ratings downgrade is on government borrowing, and while the US does borrow vast amounts, private capital (in the form of equity and debt) is a far bigger source of financing and funding for the economy.

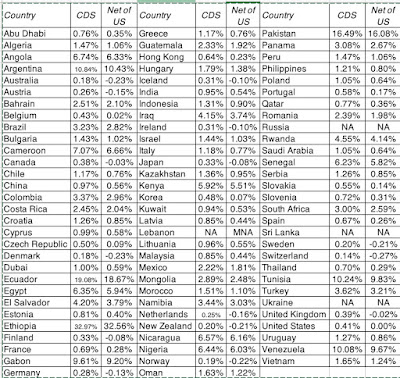

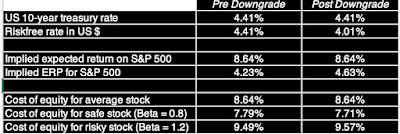

- Ratings change : The ratings downgrade ws more of a blow to pride than to finances, since the default risk (and default spread) difference between an Aaa rating and a Aa1 rating is small. Austria and Finland, for instance, had Aa1 ratings in May 2025, and their ten-year bonds, denominated in Euros, traded at a spread of about 0.15- 0.20% over the German ten-year Euro bond; Germany had a Aaa rating.

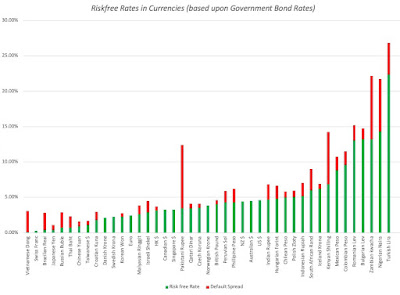

Risk free rate = Government Bond rate − Default spread for the government

- US 10-year treasury bond rate on May 30, 2025 = 4.41%

- Default spread based on Aa1 rating on May 30, 2025 = 0.40%

- Riskfree rate in US dollars on May 30, 2025 = US 10-year treasury rate - Aa1 default spread = 4.41% - 0.40% = 4.01%