October 16, 2018

Author, consultant and public speaker on momentum investing

Extended Backtest of Global Equities Momentum

In 2013, I created my Global Equities Momentum (GEM) model that applied dual momentum to stock and bond indices. We hold U.S. or non-U.S. stock indices when stocks are strong. Bonds are a safe harbor when stocks are weak.

When my book was published in 2014, I had Barclays bond index data back to 1973. Since one year of data is needed to initialize the model, GEM results were from 1974 through 2013. In 2015, I gained access to Ibbotson Intermediate Government bond data. This let me extend GEM back to 1970.

The extra bond data let us see how GEM performed during the 1973-74 bear market. GEM was up 20% those two years, while the S&P 500 index was down over 40%. This was a short out-of-sample validation of our dual momentum approach.

I thought 1971 was as far back as I could ever take GEM because MSCI non-U.S. stock index data only went back to 1970. But I recently obtained longer-term Global Financial Data (GFD) of non-U.S. stock indices. It is not as robust as cap-weighted MSCI data. Before 1970, GFD uses fixed country weights that adjust periodically. But it would still be interesting to see how GEM looks with the earlier GFD data compared to GEM since 1971.

Global Investing

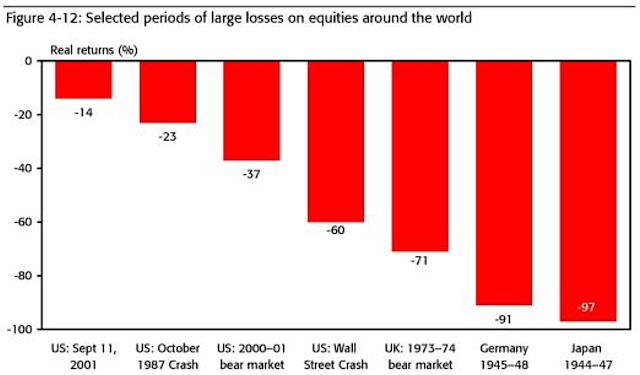

We usually want as much data as we can get to confirm an investment strategy. But we also have to consider how realistic our results will be under earlier conditions. Global investing, for example, makes little sense during the two World Wars. In WWI, there were strict capital controls that made it almost impossible to invest globally. These eased up some during the 1920s. But they strengthened again during the Great Depression. During WW II, they were the strongest they had ever been.

Even if you could have invested globally then, it would have made little sense. Imagine a U.S. investor going to a cocktail party and saying you bought German, Italian, or Japanese stocks. You would never get invited to another party. If you were an institutional investor, you would lose all your clients.

Global investing would have also been imprudent and very high risk. Right after WW II, German stocks lost 91% of their value, and Japanese stocks fell 97%.

Source: Dimson, Marsh & Staunton (2002), Triumph of the Optimists: 101 Years of Global Investment Returns

So, what is a good starting date for global investing? The first academic paper to point out the benefits of international investing was in 1968 [1]. There were similar papers in 1970 and 1974 [2]. The first mutual fund to make global investing available to U.S. investors was Templeton Growth that began in 1954. Asness, Israelov, and Liew (2017) in “ International Diversification Works (Eventually) ” used 1950 as their starting date. This seems reasonable. We will use January 1949 as the starting date of our data. GEM results can then begin on January 1950.

Data Sources

We use the S&P 500 index for U.S. stocks. For non-U.S. stocks, we use the MSCI All Country World Index ex-U.S. from its start date in January 1989. It includes both developed and emerging markets. Before 1989, we use the MSCI World Index ex-U.S. from its start date of January 1970, and GFD World Index ex-U.S. before then. These indices include only developed markets. For bonds, we use the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index from its start in January 1973. It holds investment grade (70% government) bonds with an average duration of 5 to 6 years. Before 1973, we use the Ibbotson Intermediate Government Index that holds 5 government year bonds.

GEM Model

When the trend of stocks is up according to absolute momentum applied to the S&P 500, we use relative strength momentum to determine if we will be in U.S. or non-U.S. stocks. When the trend of stocks is down, we invest in bonds. We use a 12-month look back period and rebalance monthly. A 12-month look back was effective in Cowles & Jones’ 1937 study . It also worked well in Jegadeesh & Titman’s (1993) seminal momentum research . For more about GEM, see my book .

GEM Results

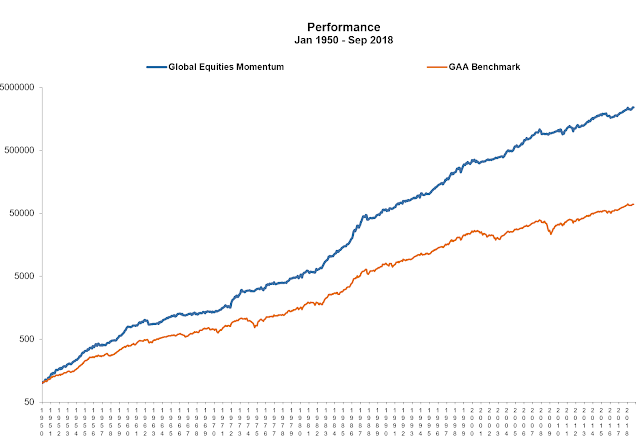

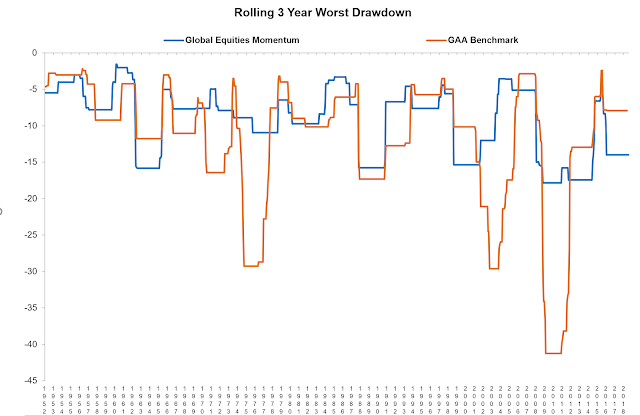

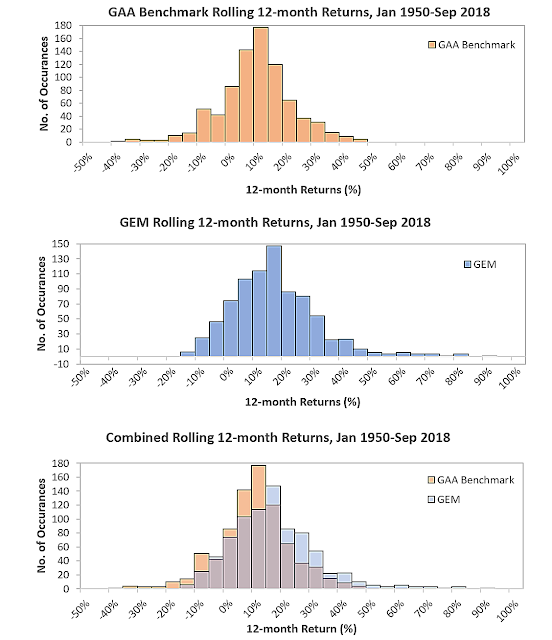

Here are GEM results compared to a global asset allocation benchmark of 45% U.S. stocks, 28% non-U.S. stocks, and 27% 5-year bonds. This is the amount of time GEM was in each of these markets. It is also representative of a typical global asset allocation portfolio.

Jan 1950 - Sep 2108 Jan 1950 - Dec 1979 Jan 1980 - Sep 2018

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our

Disclaimer

page for more information.

These results are updated monthly on the Performance pages of my website.

Relative versus Absolute Momentum

To better understand what is going on within GEM, I separated out its two components, relative and absolute momentum.

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

Relative momentum is where we switch between U.S. and non-U.S. stocks based on their relative strength. It still suffers from equity-like drawdowns. But for investors with a mandate to always be in equities, relative momentum gave 200 basis points more in annual return than the S&P 500.

Absolute momentum has 90 basis points more in annual return than the S&P 500. Its lower return than relative momentum is due to occasional whipsaws and to lags in getting in or out of equities at their turning points. But absolute momentum shows greatly reduced drawdowns.

There is synergy in combining both types of momentum. Their combined whole is greater than the sum of their parts. If you reduce bear market exposure using absolute momentum, you gain more from relative momentum in bull markets. For example, the average bear market loss of the S&P 500 index since 1950 is 33%. It takes a 50% gain to recoup that size loss, and the stock market gains about 10% per year. So, it can take 5 years on average to reach breakeven. If absolute momentum reduces bear market losses, then bull market gains become new profits instead of making up these losses. That is why GEM shows an impressive 440 basis point increase in annual return above the S&P 500 from 1950 until now, versus 200 basis points for relative momentum and 90 basis points for absolute momentum. Like absolute momentum, GEM returns were achieved with considerably reduced downside exposure.

Here are tables showing how absolute and relative momentum performed during bull and bear markets.

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

Absolute momentum gave less profit than the S&P 500 during bull markets. But dual momentum-based GEM produced more profit. Relative momentum suffered nearly the same bear market losses as the S&P 500. But GEM, over the long run, eliminated those losses.

Core Versus Satellite

With the growth of factor-based investing, more investors are willing to use momentum in their portfolios. Trend following has also been gaining traction. Academic research on trend over the past few years as shown here , has switched from skepticism to acceptance.

More often than not, those who invest in momentum or trend treat it as a satellite rather than a core holding. This may be due to anchoring, familiarity bias, or home country bias in the case of global investing. It may also be due to long-standing prejudice against timing market entries and exits. Burton Malkiel , a well-known proponent of efficient markets, once said, “Don’t try to time the market. Nothing could be more dangerous.”

For investment professionals, there is also career risk. All strategies that diverge from the market will at times underperform. If you lose money when everyone else is losing money, you will likely hold on to your clients. But if you are doing something different and lose money when others do not, there is a chance clients who are not well-educated about quantitative models will leave.

Whatever the reasons for caution, it might be helpful to see the allocation results of combining GEM with the GAA portfolio over 68 years of data.

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

[1] Grubel (1968), “ Internationally Diversified Portfolios: Welfare Gains and Capital Flows ”

[2] Levy & Sarnat (1970), “ International Diversification of Investment Portfolios ,” Solnik (1974), " Why Not Diversify Internationally Rather Than Domestically? ”

When my book was published in 2014, I had Barclays bond index data back to 1973. Since one year of data is needed to initialize the model, GEM results were from 1974 through 2013. In 2015, I gained access to Ibbotson Intermediate Government bond data. This let me extend GEM back to 1970.

The extra bond data let us see how GEM performed during the 1973-74 bear market. GEM was up 20% those two years, while the S&P 500 index was down over 40%. This was a short out-of-sample validation of our dual momentum approach.

I thought 1971 was as far back as I could ever take GEM because MSCI non-U.S. stock index data only went back to 1970. But I recently obtained longer-term Global Financial Data (GFD) of non-U.S. stock indices. It is not as robust as cap-weighted MSCI data. Before 1970, GFD uses fixed country weights that adjust periodically. But it would still be interesting to see how GEM looks with the earlier GFD data compared to GEM since 1971.

Global Investing

We usually want as much data as we can get to confirm an investment strategy. But we also have to consider how realistic our results will be under earlier conditions. Global investing, for example, makes little sense during the two World Wars. In WWI, there were strict capital controls that made it almost impossible to invest globally. These eased up some during the 1920s. But they strengthened again during the Great Depression. During WW II, they were the strongest they had ever been.

Even if you could have invested globally then, it would have made little sense. Imagine a U.S. investor going to a cocktail party and saying you bought German, Italian, or Japanese stocks. You would never get invited to another party. If you were an institutional investor, you would lose all your clients.

Global investing would have also been imprudent and very high risk. Right after WW II, German stocks lost 91% of their value, and Japanese stocks fell 97%.

Source: Dimson, Marsh & Staunton (2002), Triumph of the Optimists: 101 Years of Global Investment Returns

So, what is a good starting date for global investing? The first academic paper to point out the benefits of international investing was in 1968 [1]. There were similar papers in 1970 and 1974 [2]. The first mutual fund to make global investing available to U.S. investors was Templeton Growth that began in 1954. Asness, Israelov, and Liew (2017) in “ International Diversification Works (Eventually) ” used 1950 as their starting date. This seems reasonable. We will use January 1949 as the starting date of our data. GEM results can then begin on January 1950.

Data Sources

We use the S&P 500 index for U.S. stocks. For non-U.S. stocks, we use the MSCI All Country World Index ex-U.S. from its start date in January 1989. It includes both developed and emerging markets. Before 1989, we use the MSCI World Index ex-U.S. from its start date of January 1970, and GFD World Index ex-U.S. before then. These indices include only developed markets. For bonds, we use the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index from its start in January 1973. It holds investment grade (70% government) bonds with an average duration of 5 to 6 years. Before 1973, we use the Ibbotson Intermediate Government Index that holds 5 government year bonds.

GEM Model

When the trend of stocks is up according to absolute momentum applied to the S&P 500, we use relative strength momentum to determine if we will be in U.S. or non-U.S. stocks. When the trend of stocks is down, we invest in bonds. We use a 12-month look back period and rebalance monthly. A 12-month look back was effective in Cowles & Jones’ 1937 study . It also worked well in Jegadeesh & Titman’s (1993) seminal momentum research . For more about GEM, see my book .

GEM Results

Here are GEM results compared to a global asset allocation benchmark of 45% U.S. stocks, 28% non-U.S. stocks, and 27% 5-year bonds. This is the amount of time GEM was in each of these markets. It is also representative of a typical global asset allocation portfolio.

Jan 1950 - Sep 2108 Jan 1950 - Dec 1979 Jan 1980 - Sep 2018

GEM

| GAA

| GEM

| GAA

| GEM

| GAA

| |

CAGR

| 15.8

| 10.0

| 13.9

| 9.6

| 17.3

| 10.3

|

Annual Std Dev

| 11.5

| 9.8

| 10.2

| 8.3

| 12.4

| 10.9

|

Skewness

| -0.09

| -0.54

| 0.30

| -0.24

| -0.29

| -0.63

|

Sharpe Ratio

| 0.96

| 0.57

| 0.72

| 0.39

| 1.03

| 0.58

|

Worst Drawdown

| -17.8

| -41.2

| -15.8

| -29.3

| -17.8

| -41.2

|

Worst 6 Months

| -15.7

| -33.0

| -15.7

| -21.0

| -15.0

| -33.0

|

Worst 12 Months

| -17.8

| -35.7

| -13.3

| -28.1

| -17.8

| -35.7

|

% of Profit Months

| 69

| 67

| 67

| 68

| 72

| 63

|

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

These results are updated monthly on the Performance pages of my website.

Relative versus Absolute Momentum

To better understand what is going on within GEM, I separated out its two components, relative and absolute momentum.

GEM

| REL MOM

| ABS MOM

| S&P 500

| |

CAGR

| 15.8

| 13.4

| 12.3

| 11.4

|

Annual Std Dev

| 11.5

| 14.4

| 11.2

| 14.2

|

Sharpe Ratio

| 0.96

| 0.64

| 0.7

| 0.52

|

Worst Drawdown

| -17.8

| -54.6

| -29.6

| -51.0

|

Worst 6 Months

| -15.7

| -41.8

| -25.2

| -41.8

|

Worst 12 Months

| -17.8

| -48.1

| -25.3

| -43.3

|

% of Profit Months

| 69

| 65

| 67

| 64

|

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

Relative momentum is where we switch between U.S. and non-U.S. stocks based on their relative strength. It still suffers from equity-like drawdowns. But for investors with a mandate to always be in equities, relative momentum gave 200 basis points more in annual return than the S&P 500.

Absolute momentum has 90 basis points more in annual return than the S&P 500. Its lower return than relative momentum is due to occasional whipsaws and to lags in getting in or out of equities at their turning points. But absolute momentum shows greatly reduced drawdowns.

There is synergy in combining both types of momentum. Their combined whole is greater than the sum of their parts. If you reduce bear market exposure using absolute momentum, you gain more from relative momentum in bull markets. For example, the average bear market loss of the S&P 500 index since 1950 is 33%. It takes a 50% gain to recoup that size loss, and the stock market gains about 10% per year. So, it can take 5 years on average to reach breakeven. If absolute momentum reduces bear market losses, then bull market gains become new profits instead of making up these losses. That is why GEM shows an impressive 440 basis point increase in annual return above the S&P 500 from 1950 until now, versus 200 basis points for relative momentum and 90 basis points for absolute momentum. Like absolute momentum, GEM returns were achieved with considerably reduced downside exposure.

Here are tables showing how absolute and relative momentum performed during bull and bear markets.

BULL MARKETS

| S&P 500

| Abs Mom

| GEM

|

Jan 1950- Dec 1961

| 647.7

| 608.3

| 1014.6

|

Jul 1962- Nov 1968

| 143.7

| 66.7

| 58.0

|

Jul 1970- Dec 1972

| 75.6

| 47.2

| 84.0

|

Oct 1974- Dec 1980

| 198.3

| 91.6

| 103.3

|

Aug 1982-Aug 1987

| 279.7

| 246.3

| 569.2

|

Dec 1987- Aug 2000

| 816.6

| 728.4

| 730.5

|

Oct 2002-Oct 2007

| 108.3

| 72.4

| 181.6

|

Mar 2009-Dec 2017

| 338.7

| 177.4

| 142.3

|

AVERAGE

| 326.1

| 254.8

| 360.4

|

BEAR MARKETS

| S&P 500

| Rel Mom

| GEM

|

Jan 1962- Jun 1962

| -22.8

| -18.5

| -15.7

|

Dec 1968- Jun 1970

| -29.3

| -13.9

|

4.3

|

Jan 1973- Sep 1974

| -42.6

| -35.6

|

15.1

|

Dec 1980- Jul 1982

| -16.5

| -16.9

|

16.0

|

Sep 1987- Nov 1987

| -29.6

| -15.1

|

15.1

|

Sep 2000- Sep 2002

| -44.7

| -43.4

|

14.9

|

Nov 2007-Feb 2009

| -50.9

| -54.6

| -13.1

|

AVERAGE

| -33.8

| -28.3

|

0.9

|

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

Absolute momentum gave less profit than the S&P 500 during bull markets. But dual momentum-based GEM produced more profit. Relative momentum suffered nearly the same bear market losses as the S&P 500. But GEM, over the long run, eliminated those losses.

Core Versus Satellite

With the growth of factor-based investing, more investors are willing to use momentum in their portfolios. Trend following has also been gaining traction. Academic research on trend over the past few years as shown here , has switched from skepticism to acceptance.

More often than not, those who invest in momentum or trend treat it as a satellite rather than a core holding. This may be due to anchoring, familiarity bias, or home country bias in the case of global investing. It may also be due to long-standing prejudice against timing market entries and exits. Burton Malkiel , a well-known proponent of efficient markets, once said, “Don’t try to time the market. Nothing could be more dangerous.”

For investment professionals, there is also career risk. All strategies that diverge from the market will at times underperform. If you lose money when everyone else is losing money, you will likely hold on to your clients. But if you are doing something different and lose money when others do not, there is a chance clients who are not well-educated about quantitative models will leave.

Whatever the reasons for caution, it might be helpful to see the allocation results of combining GEM with the GAA portfolio over 68 years of data.

GEM

| 75%/25%

| 50%/50%

| 25%/75%

|

GAA

| |

CAGR

| 15.8

| 14.4

| 13.0

| 11.5

| 10.0

|

Annual Std Dev

| 11.5

| 10.4

| 9.8

| 9.7

| 9.8

|

Sharpe Ratio

| 0.96

| 0.92

| 0.85

| 0.73

| 0.57

|

Worst Drawdown

| -17.8

| -21.2

| -28.1

| -34.9

| -41.2

|

Worst 6 Months

| -15.7

| -14.6

| -17.0

| -25.3

| -33.0

|

Worst 12 Months

| -17.8

| -21.2

| -24.6

| -28.0

| -35.7

|

% of Profit Months

| 69

| 69

| 68

| 68

| 67

|

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

[1] Grubel (1968), “ Internationally Diversified Portfolios: Welfare Gains and Capital Flows ”

[2] Levy & Sarnat (1970), “ International Diversification of Investment Portfolios ,” Solnik (1974), " Why Not Diversify Internationally Rather Than Domestically? ”

In 2013, I created my Global Equities Momentum (GEM) model that applied dual momentum to stock and bond indices. We hold U.S. or non-U.S. stock indices when stocks are strong. Bonds are a safe harbor when stocks are weak.

When my book was published in 2014, I had Barclays bond index data back to 1973. Since one year of data is needed to initialize the model, GEM results were from 1974 through 2013. In 2015, I gained access to Ibbotson Intermediate Government bond data. This let me extend GEM back to 1970.

The extra bond data let us see how GEM performed during the 1973-74 bear market. GEM was up 20% those two years, while the S&P 500 index was down over 40%. This was a short out-of-sample validation of our dual momentum approach.

I thought 1971 was as far back as I could ever take GEM because MSCI non-U.S. stock index data only went back to 1970. But I recently obtained longer-term Global Financial Data (GFD) of non-U.S. stock indices. It is not as robust as cap-weighted MSCI data. Before 1970, GFD uses fixed country weights that adjust periodically. But it would still be interesting to see how GEM looks with the earlier GFD data compared to GEM since 1971.

Global Investing

We usually want as much data as we can get to confirm an investment strategy. But we also have to consider how realistic our results will be under earlier conditions. Global investing, for example, makes little sense during the two World Wars. In WWI, there were strict capital controls that made it almost impossible to invest globally. These eased up some during the 1920s. But they strengthened again during the Great Depression. During WW II, they were the strongest they had ever been.

Even if you could have invested globally then, it would have made little sense. Imagine a U.S. investor going to a cocktail party and saying you bought German, Italian, or Japanese stocks. You would never get invited to another party. If you were an institutional investor, you would lose all your clients.

Global investing would have also been imprudent and very high risk. Right after WW II, German stocks lost 91% of their value, and Japanese stocks fell 97%.

Source: Dimson, Marsh & Staunton (2002), Triumph of the Optimists: 101 Years of Global Investment Returns

So, what is a good starting date for global investing? The first academic paper to point out the benefits of international investing was in 1968 [1]. There were similar papers in 1970 and 1974 [2]. The first mutual fund to make global investing available to U.S. investors was Templeton Growth that began in 1954. Asness, Israelov, and Liew (2017) in “ International Diversification Works (Eventually) ” used 1950 as their starting date. This seems reasonable. We will use January 1949 as the starting date of our data. GEM results can then begin on January 1950.

Data Sources

We use the S&P 500 index for U.S. stocks. For non-U.S. stocks, we use the MSCI All Country World Index ex-U.S. from its start date in January 1989. It includes both developed and emerging markets. Before 1989, we use the MSCI World Index ex-U.S. from its start date of January 1970, and GFD World Index ex-U.S. before then. These indices include only developed markets. For bonds, we use the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index from its start in January 1973. It holds investment grade (70% government) bonds with an average duration of 5 to 6 years. Before 1973, we use the Ibbotson Intermediate Government Index that holds 5 government year bonds.

GEM Model

When the trend of stocks is up according to absolute momentum applied to the S&P 500, we use relative strength momentum to determine if we will be in U.S. or non-U.S. stocks. When the trend of stocks is down, we invest in bonds. We use a 12-month look back period and rebalance monthly. A 12-month look back was effective in Cowles & Jones’ 1937 study . It also worked well in Jegadeesh & Titman’s (1993) seminal momentum research . For more about GEM, see my book .

GEM Results

Here are GEM results compared to a global asset allocation benchmark of 45% U.S. stocks, 28% non-U.S. stocks, and 27% 5-year bonds. This is the amount of time GEM was in each of these markets. It is also representative of a typical global asset allocation portfolio.

Jan 1950 - Sep 2108 Jan 1950 - Dec 1979 Jan 1980 - Sep 2018

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our

Disclaimer

page for more information.

These results are updated monthly on the Performance pages of my website.

Relative versus Absolute Momentum

To better understand what is going on within GEM, I separated out its two components, relative and absolute momentum.

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

Relative momentum is where we switch between U.S. and non-U.S. stocks based on their relative strength. It still suffers from equity-like drawdowns. But for investors with a mandate to always be in equities, relative momentum gave 200 basis points more in annual return than the S&P 500.

Absolute momentum has 90 basis points more in annual return than the S&P 500. Its lower return than relative momentum is due to occasional whipsaws and to lags in getting in or out of equities at their turning points. But absolute momentum shows greatly reduced drawdowns.

There is synergy in combining both types of momentum. Their combined whole is greater than the sum of their parts. If you reduce bear market exposure using absolute momentum, you gain more from relative momentum in bull markets. For example, the average bear market loss of the S&P 500 index since 1950 is 33%. It takes a 50% gain to recoup that size loss, and the stock market gains about 10% per year. So, it can take 5 years on average to reach breakeven. If absolute momentum reduces bear market losses, then bull market gains become new profits instead of making up these losses. That is why GEM shows an impressive 440 basis point increase in annual return above the S&P 500 from 1950 until now, versus 200 basis points for relative momentum and 90 basis points for absolute momentum. Like absolute momentum, GEM returns were achieved with considerably reduced downside exposure.

Here are tables showing how absolute and relative momentum performed during bull and bear markets.

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

Absolute momentum gave less profit than the S&P 500 during bull markets. But dual momentum-based GEM produced more profit. Relative momentum suffered nearly the same bear market losses as the S&P 500. But GEM, over the long run, eliminated those losses.

Core Versus Satellite

With the growth of factor-based investing, more investors are willing to use momentum in their portfolios. Trend following has also been gaining traction. Academic research on trend over the past few years as shown here , has switched from skepticism to acceptance.

More often than not, those who invest in momentum or trend treat it as a satellite rather than a core holding. This may be due to anchoring, familiarity bias, or home country bias in the case of global investing. It may also be due to long-standing prejudice against timing market entries and exits. Burton Malkiel , a well-known proponent of efficient markets, once said, “Don’t try to time the market. Nothing could be more dangerous.”

For investment professionals, there is also career risk. All strategies that diverge from the market will at times underperform. If you lose money when everyone else is losing money, you will likely hold on to your clients. But if you are doing something different and lose money when others do not, there is a chance clients who are not well-educated about quantitative models will leave.

Whatever the reasons for caution, it might be helpful to see the allocation results of combining GEM with the GAA portfolio over 68 years of data.

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

[1] Grubel (1968), “ Internationally Diversified Portfolios: Welfare Gains and Capital Flows ”

[2] Levy & Sarnat (1970), “ International Diversification of Investment Portfolios ,” Solnik (1974), " Why Not Diversify Internationally Rather Than Domestically? ”

When my book was published in 2014, I had Barclays bond index data back to 1973. Since one year of data is needed to initialize the model, GEM results were from 1974 through 2013. In 2015, I gained access to Ibbotson Intermediate Government bond data. This let me extend GEM back to 1970.

The extra bond data let us see how GEM performed during the 1973-74 bear market. GEM was up 20% those two years, while the S&P 500 index was down over 40%. This was a short out-of-sample validation of our dual momentum approach.

I thought 1971 was as far back as I could ever take GEM because MSCI non-U.S. stock index data only went back to 1970. But I recently obtained longer-term Global Financial Data (GFD) of non-U.S. stock indices. It is not as robust as cap-weighted MSCI data. Before 1970, GFD uses fixed country weights that adjust periodically. But it would still be interesting to see how GEM looks with the earlier GFD data compared to GEM since 1971.

Global Investing

We usually want as much data as we can get to confirm an investment strategy. But we also have to consider how realistic our results will be under earlier conditions. Global investing, for example, makes little sense during the two World Wars. In WWI, there were strict capital controls that made it almost impossible to invest globally. These eased up some during the 1920s. But they strengthened again during the Great Depression. During WW II, they were the strongest they had ever been.

Even if you could have invested globally then, it would have made little sense. Imagine a U.S. investor going to a cocktail party and saying you bought German, Italian, or Japanese stocks. You would never get invited to another party. If you were an institutional investor, you would lose all your clients.

Global investing would have also been imprudent and very high risk. Right after WW II, German stocks lost 91% of their value, and Japanese stocks fell 97%.

Source: Dimson, Marsh & Staunton (2002), Triumph of the Optimists: 101 Years of Global Investment Returns

So, what is a good starting date for global investing? The first academic paper to point out the benefits of international investing was in 1968 [1]. There were similar papers in 1970 and 1974 [2]. The first mutual fund to make global investing available to U.S. investors was Templeton Growth that began in 1954. Asness, Israelov, and Liew (2017) in “ International Diversification Works (Eventually) ” used 1950 as their starting date. This seems reasonable. We will use January 1949 as the starting date of our data. GEM results can then begin on January 1950.

Data Sources

We use the S&P 500 index for U.S. stocks. For non-U.S. stocks, we use the MSCI All Country World Index ex-U.S. from its start date in January 1989. It includes both developed and emerging markets. Before 1989, we use the MSCI World Index ex-U.S. from its start date of January 1970, and GFD World Index ex-U.S. before then. These indices include only developed markets. For bonds, we use the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index from its start in January 1973. It holds investment grade (70% government) bonds with an average duration of 5 to 6 years. Before 1973, we use the Ibbotson Intermediate Government Index that holds 5 government year bonds.

GEM Model

When the trend of stocks is up according to absolute momentum applied to the S&P 500, we use relative strength momentum to determine if we will be in U.S. or non-U.S. stocks. When the trend of stocks is down, we invest in bonds. We use a 12-month look back period and rebalance monthly. A 12-month look back was effective in Cowles & Jones’ 1937 study . It also worked well in Jegadeesh & Titman’s (1993) seminal momentum research . For more about GEM, see my book .

GEM Results

Here are GEM results compared to a global asset allocation benchmark of 45% U.S. stocks, 28% non-U.S. stocks, and 27% 5-year bonds. This is the amount of time GEM was in each of these markets. It is also representative of a typical global asset allocation portfolio.

Jan 1950 - Sep 2108 Jan 1950 - Dec 1979 Jan 1980 - Sep 2018

GEM

| GAA

| GEM

| GAA

| GEM

| GAA

| |

CAGR

| 15.8

| 10.0

| 13.9

| 9.6

| 17.3

| 10.3

|

Annual Std Dev

| 11.5

| 9.8

| 10.2

| 8.3

| 12.4

| 10.9

|

Skewness

| -0.09

| -0.54

| 0.30

| -0.24

| -0.29

| -0.63

|

Sharpe Ratio

| 0.96

| 0.57

| 0.72

| 0.39

| 1.03

| 0.58

|

Worst Drawdown

| -17.8

| -41.2

| -15.8

| -29.3

| -17.8

| -41.2

|

Worst 6 Months

| -15.7

| -33.0

| -15.7

| -21.0

| -15.0

| -33.0

|

Worst 12 Months

| -17.8

| -35.7

| -13.3

| -28.1

| -17.8

| -35.7

|

% of Profit Months

| 69

| 67

| 67

| 68

| 72

| 63

|

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

These results are updated monthly on the Performance pages of my website.

Relative versus Absolute Momentum

To better understand what is going on within GEM, I separated out its two components, relative and absolute momentum.

GEM

| REL MOM

| ABS MOM

| S&P 500

| |

CAGR

| 15.8

| 13.4

| 12.3

| 11.4

|

Annual Std Dev

| 11.5

| 14.4

| 11.2

| 14.2

|

Sharpe Ratio

| 0.96

| 0.64

| 0.7

| 0.52

|

Worst Drawdown

| -17.8

| -54.6

| -29.6

| -51.0

|

Worst 6 Months

| -15.7

| -41.8

| -25.2

| -41.8

|

Worst 12 Months

| -17.8

| -48.1

| -25.3

| -43.3

|

% of Profit Months

| 69

| 65

| 67

| 64

|

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

Relative momentum is where we switch between U.S. and non-U.S. stocks based on their relative strength. It still suffers from equity-like drawdowns. But for investors with a mandate to always be in equities, relative momentum gave 200 basis points more in annual return than the S&P 500.

Absolute momentum has 90 basis points more in annual return than the S&P 500. Its lower return than relative momentum is due to occasional whipsaws and to lags in getting in or out of equities at their turning points. But absolute momentum shows greatly reduced drawdowns.

There is synergy in combining both types of momentum. Their combined whole is greater than the sum of their parts. If you reduce bear market exposure using absolute momentum, you gain more from relative momentum in bull markets. For example, the average bear market loss of the S&P 500 index since 1950 is 33%. It takes a 50% gain to recoup that size loss, and the stock market gains about 10% per year. So, it can take 5 years on average to reach breakeven. If absolute momentum reduces bear market losses, then bull market gains become new profits instead of making up these losses. That is why GEM shows an impressive 440 basis point increase in annual return above the S&P 500 from 1950 until now, versus 200 basis points for relative momentum and 90 basis points for absolute momentum. Like absolute momentum, GEM returns were achieved with considerably reduced downside exposure.

Here are tables showing how absolute and relative momentum performed during bull and bear markets.

BULL MARKETS

| S&P 500

| Abs Mom

| GEM

|

Jan 1950- Dec 1961

| 647.7

| 608.3

| 1014.6

|

Jul 1962- Nov 1968

| 143.7

| 66.7

| 58.0

|

Jul 1970- Dec 1972

| 75.6

| 47.2

| 84.0

|

Oct 1974- Dec 1980

| 198.3

| 91.6

| 103.3

|

Aug 1982-Aug 1987

| 279.7

| 246.3

| 569.2

|

Dec 1987- Aug 2000

| 816.6

| 728.4

| 730.5

|

Oct 2002-Oct 2007

| 108.3

| 72.4

| 181.6

|

Mar 2009-Dec 2017

| 338.7

| 177.4

| 142.3

|

AVERAGE

| 326.1

| 254.8

| 360.4

|

BEAR MARKETS

| S&P 500

| Rel Mom

| GEM

|

Jan 1962- Jun 1962

| -22.8

| -18.5

| -15.7

|

Dec 1968- Jun 1970

| -29.3

| -13.9

|

4.3

|

Jan 1973- Sep 1974

| -42.6

| -35.6

|

15.1

|

Dec 1980- Jul 1982

| -16.5

| -16.9

|

16.0

|

Sep 1987- Nov 1987

| -29.6

| -15.1

|

15.1

|

Sep 2000- Sep 2002

| -44.7

| -43.4

|

14.9

|

Nov 2007-Feb 2009

| -50.9

| -54.6

| -13.1

|

AVERAGE

| -33.8

| -28.3

|

0.9

|

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

Absolute momentum gave less profit than the S&P 500 during bull markets. But dual momentum-based GEM produced more profit. Relative momentum suffered nearly the same bear market losses as the S&P 500. But GEM, over the long run, eliminated those losses.

Core Versus Satellite

With the growth of factor-based investing, more investors are willing to use momentum in their portfolios. Trend following has also been gaining traction. Academic research on trend over the past few years as shown here , has switched from skepticism to acceptance.

More often than not, those who invest in momentum or trend treat it as a satellite rather than a core holding. This may be due to anchoring, familiarity bias, or home country bias in the case of global investing. It may also be due to long-standing prejudice against timing market entries and exits. Burton Malkiel , a well-known proponent of efficient markets, once said, “Don’t try to time the market. Nothing could be more dangerous.”

For investment professionals, there is also career risk. All strategies that diverge from the market will at times underperform. If you lose money when everyone else is losing money, you will likely hold on to your clients. But if you are doing something different and lose money when others do not, there is a chance clients who are not well-educated about quantitative models will leave.

Whatever the reasons for caution, it might be helpful to see the allocation results of combining GEM with the GAA portfolio over 68 years of data.

GEM

| 75%/25%

| 50%/50%

| 25%/75%

|

GAA

| |

CAGR

| 15.8

| 14.4

| 13.0

| 11.5

| 10.0

|

Annual Std Dev

| 11.5

| 10.4

| 9.8

| 9.7

| 9.8

|

Sharpe Ratio

| 0.96

| 0.92

| 0.85

| 0.73

| 0.57

|

Worst Drawdown

| -17.8

| -21.2

| -28.1

| -34.9

| -41.2

|

Worst 6 Months

| -15.7

| -14.6

| -17.0

| -25.3

| -33.0

|

Worst 12 Months

| -17.8

| -21.2

| -24.6

| -28.0

| -35.7

|

% of Profit Months

| 69

| 69

| 68

| 68

| 67

|

Results are hypothetical, are NOT an indicator of future results, and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Please see our Disclaimer page for more information.

[1] Grubel (1968), “ Internationally Diversified Portfolios: Welfare Gains and Capital Flows ”

[2] Levy & Sarnat (1970), “ International Diversification of Investment Portfolios ,” Solnik (1974), " Why Not Diversify Internationally Rather Than Domestically? ”

RSS Import: Original Source

More from Gary Antonacci

The most important insight of the day

Get the Harvest Daily Digest newsletter.