Challenges to China’s Growth

China has shown impressive economic growth during the past 40 years, driven largely by the opening of the country to foreign investment. While these initiatives have helped make China one of the world’s leading engines of innovation and growth, there are several significant challenges on the horizon.

The challenges do not necessarily undermine China’s long-term appeal as a macro play, but should nonetheless be taken into consideration by investors taking a top-down view of the investment opportunities.

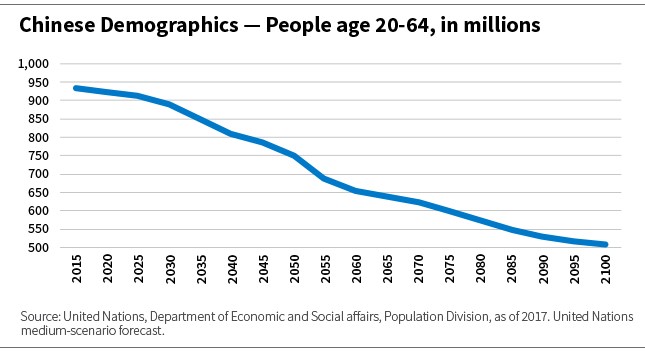

Demographics: Contracting Working Population

Demographic shifts are going to have a major impact on growth, productivity, and strategic decisions by Chinese companies.

China’s working population is expected to decrease by 12% from 2020 to 2040, according to United Nations projections. This is due only in part to the one-child policy—first relaxed and then eliminated in 2015—after which the Chinese have continued to show a preference for smaller families. This drop is on par with Germany and worse than some European countries, such as Sweden, which is expected to see a 4% increase in its working population during that same period. Some Asian countries are looking even better. In Malaysia and Pakistan, for example, the working populations are expected to grow by double digits, by 50% in Pakistan and 25% in Malaysia during the same period.

An aging population and shrinking workforce domestically are compelling Chinese companies to expand their presence in countries with more favorable demographic trends, such as Pakistan and Malaysia.

Considering the aging of China’s population, it makes sense that Chinese companies would want to expand in countries with an abundance of labor and growing consumer bases. This makes the aging population and shrinking workforce one of the drivers for China’s international expansion.

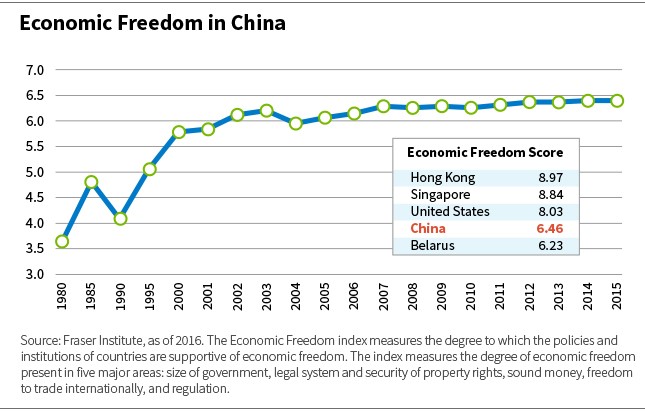

Economic Freedom: Stalling Progress

Between 1990 and 2000, China moved up quickly in the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom index, which measures the degree to which policies and institutions of countries support economic freedom, taking into account the legal system, property rights, openness to trade, and monetary policy.

Since that jump, however, China’s progress stalled. With a score of 6.46 as of 2016, China is much closer to Belarus (6.23) than the United States (8.03).

After making impressive gains in economic freedom in the 1990s, China’s progress has stalled over the past 15 years.

That leaves room for improvement, and there is hope that China will move up in the index as the government continues to open the country’s capital markets.

Recent developments include the Bond Connect, which allows investors from mainland China and overseas to trade in each other’s bond markets, and Stock Connect, a collaboration among the Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Shenzhen stock exchanges that allows international and mainland Chinese investors to trade securities in each other’s markets.

Corruption and Debt: Looking Behind the Numbers

Corruption and debt in China are concerns commonly cited by potential foreign investors.

On the corruption front, we see the glass as half full. China ranks 77 out of 180 countries in the 2017 Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. A ranking closer to 1 means the company is perceived to be less corrupt. While China is ranked significantly worse than the United States (16), it is ranked significantly better than both Brazil (96) and Mexico (135). Investors thus have more reason to cite corruption as a reason not to invest in Mexico than in China.

China’s credit situation does not look alarming compared with countries such as the United States, Korea, and Japan, but the trajectory raises concerns. Credit and debt levels in the country have grown significantly during the past decade. This raises questions about the degree to which China’s leverage load will serve as a headwind to economic growth, especially among households.

China is allegedly becoming a consumption-driven economy, but part of the increased consumption has been driven by more household borrowing and increased government spending.

While China’s relatively high level of non-financial corporate debt is alarming on the surface, we believe these numbers are a bit misleading. China’s corporate debt exceeds that in most other countries, but many Chinese corporations are state-owned enterprises.

UBS has estimated that about 60% of Chinese corporate debt is actually government debt. In our view, this debt can be considered either as government debt or no debt at all, in the case a government-owned company has borrowed from the government.

On the darker side of the debt story, the actual debt levels are unknown in much the same way as off-balance-sheet obligations in the United States are difficult to estimate. Local Chinese governments have been found to manipulate their debt data, thus blurring the overall picture.

Investment Implications

China’s long-term macro outlook provides a compelling opportunity for investors as the country continues opening its capital markets to foreign investors. There are, however, significant challenges that top-down investors cannot afford to ignore.

To access more insights about how William Blair is reaching beyond traditional investment analysis to think about the white space between asset classes, sectors, geographic regions, and investment teams, we invite you to explore other posts about sessions at our 2018 CONNECTIVITY conference .

Lotta Moberg, Ph.D., is an analyst on William Blair’s Dynamic Allocation Strategies team.

RSS Import: Original Source